ICSI requires only a single sperm to be injected into each egg and is considered by many to be the greatest advance in the treatment of infertile males. In theory, it can help a man who can produce only a single sperm, and the sperm does not even need to be able to move or to be fully mature. Couples whose only previous chance of having a baby was through donor insemination can now take advantage of this treatment. It can be used to help men who have a total blockage of any part of the male tubing from the testes as sperm can be ‘sucked’ directly from the blocked tubing or from the testicle itself.

This technique may be suggested if fewer than 100,000 sperm may be capable of being retrieved for routine IVF, or in cases where very few sperm shows adequate movement. ICSI may be used if there are very abnormal sperm, provided at least four percent of sperm are normal, and there are no large sperm heads. ICSI may also be used when high levels of sperm antibodies are present, and routine sperm washing is ineffective as well as when there has been repeated fertilisation failure during a previous IVF cycle. Some patients undergoing preimplantation diagnosis for genetic defects will also be treated using ICSI and it may be considered in couples where infertility is unexplained and routine IVF has repeatedly failed.

ICSI is labour-intensive and requires considerable training and experience. It is very easy to damage the egg, and there is a considerable skill in picking up the best sperm, free from obvious defects that might prevent fertilisation.

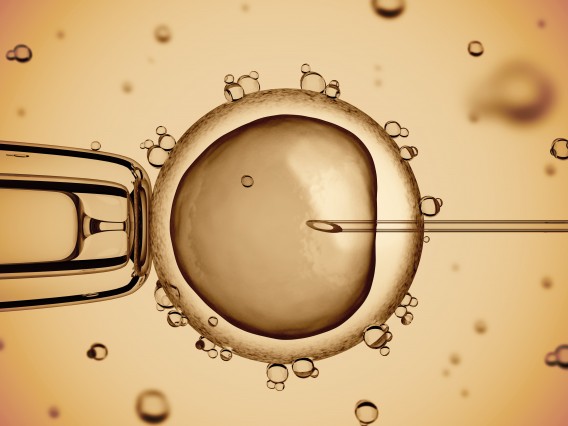

When a human egg is first collected, it is surrounded by millions of sticky ‘helper’ cells that provide essential nutrients and remove waste products. All of these cells have to be removed and, once cleaned, the egg is ready. Intracytoplasmic injection with sperm requires exquisitely delicate manipulation with fine instruments. Two types of pipette are needed. A fine holding pipette about 0.04 mm across holds the egg still using gentle suction. The second finer ‘injection’ pipette has an internal diameter hardly wider than the sperm head that it picks up, and it keeps the sperm tail immobilised. This pipette has a bevelled tip so it can penetrate the egg without disturbing the cytoplasm. Both pipettes are held rigidly in metal micromanipulators that isolate them from the operator’s hands, so allowing very precise, controlled movements. Suction through the pipettes is controlled with mounted syringes – the barrel of the syringe is attached to a screw thread. Most laboratories mount their equipment on a special table that is cushioned from shocks in a variety of ways – someone hammering in a corridor 30 m away could disturb the procedure – and they often have two sets of equipment just in case.

Picking up a sperm in such a tiny fragile glass tube is difficult, particularly if a sperm is capable of some movement, so steps are often taken to control their movement. For example, the sperm may be immersed in a viscous fluid that prevents its tail from thrashing around. The tail can then be crushed with the end of a pipette, to prevent further movement, then the sperm is sucked into the finer pipette. This tube is ‘injected’ through the egg’s outer layer (zona), and the membrane surrounding the substance of the egg (the cytoplasm) in one controlled, thrusting movement. The nucleus of the egg must be left undamaged, so care must be taken not to go right through the egg. The sperm head must be gently ‘injected’ to minimise disturbance, and the needle pipette must be withdrawn carefully. It takes several minutes to inject each egg. If a patient yields a lot of eggs this process can take over an hour.

Once the eggs have been injected, they are returned to the culture oven. They are then inspected 20-24 hours later to see if fertilisation has occurred and to assess embryonic development. If more than one egg is fertilised and they appear to be developing well, those not being transferred can be frozen. Cryopreservation is not justified unless the embryo is showing good development with mostly normal cells.

In general, the results of the treatment of male infertility using ICSI outstrip the results from all other treatments by IVF. In the UK, the HFEA (Human Fertility and Embryology Authority) claim that the success rates with ICSI are now so close to those achieved using ‘natural’ fertilisation in routine IVF that they do not report the results separately. However, there still remains some concern that children born after ICSI may be at slightly higher risk of disease in later life.

There are various theoretical risks associated with ICSI, for example:

If any of the above were true, there might be reduced fertilisation rates or reduced embryo formation. However this does not appear to be the case: both fertilisation rates and embryo formation are improved by ICSI. There could well be a reduced pregnancy rate or possibly a higher miscarriage rate, both more likely when abnormal embryos are present. There is convincing evidence, both in the UK and elsewhere, that pregnancy rates are actually higher and the incidence of miscarriage is not increased.

A key observation would be the number of babies born with an abnormality. In the UK in 1998, 42 of the babies born after IVF had an abnormality of some kind (about 0.6 percent of the total). Of these, six had an abnormality of a chromosome – mostly Down’s syndrome – and 12 babies had a heart defect (the most common defect). This overall incidence is below the incidence of abnormality seen after normal conception in fertile couples. Thirteen babies with abnormalities were born after ICSI (0.9 per cent); the most common was a kidney defect found in four babies.

Many babies have been born after ICSI worldwide and the incidence of abnormality is a little higher than in the general population. However, a somewhat higher than expected number of women have had a pregnancy terminated after ICSI for major malformations seen following antenatal diagnosis so there is a need for proper follow-up.

Whilst ICSI seems to have a low risk of causing an abnormality, any man considering undergoing ICSI, who has a low or abnormal sperm count for reasons that are not clearly established should be screened to rule out a genetic cause for the impairment. Otherwise there is always a risk that ICSI will pass the abnormality to the child. A blood sample will be taken, and a chromosome assessment known as a karyotype should reveal any abnormalities of the paired chromosomes. Although it will not rule out the transmission of an abnormality that cannot be detected, it should avoid any risk of Down’s syndrome and most other serious chromosomal defects. Screening for cystic fibrosis (looking at cells taken from a mouthwash) is also recommended.

The great majority of ICSI treatments are done using ejaculated sperm, but in some situations sperm need to be extracted by epididymal or testicular aspiration.

Development of sperm injection treatment

Work in this field began in the 1980s when researchers succeeded in fertilising mice eggs by injecting single sperm through the outer coat of the egg (the zona pellucida) and into the substance of the egg (the cytoplasm) – Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). But it was feared that the injection could damage the egg, or that an abnormal sperm might be injected. In Nottingham in the late 1980s, Dr Simon Fishel developed a technique to use on human eggs that involved injecting sperm just under the egg’s outer shell or zona, (sub-zonal sperm injection/SUZI) leaving the sperm to penetrate the cytoplasm on its own. Thought to be safer than direct injection as the egg would not be disrupted, and he could select only sperm capable of penetrating the cytoplasm. The UK authorities refused to licence a pilot scheme on humans so Fishel took his work to Italy. Soon a number of couples were giving birth to completely normal babies. SUZI would eventually be superseded by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), the method, which had originally been pioneered earlier in mice. The group who were mostly responsible for the successful development of ICSI for humans was a team lead by Professor Andre van Steirteghem at The Free University of Brussels, in Belgium.

Despite countless breakthroughs in medical science, we still do not understand why some pregnancies will end in tragedy. For most of us, having a child of our own is the most fulfilling experience of our lives. All of us can imagine the desperation and sadness of parents who lose a baby, and the life-shattering impact that a disabled or seriously ill child has on a family. Professor Robert Winston’s Genesis Research Trust raises money for the largest UK-based collection of scientists and clinicians who are researching the causes and cures for conditions that affect the health of women and babies.

Essential Parent is proud to support their wonderful work. You can learn more about them here.