The best chance of having successful treatment means you should do everything reasonable to find out the basic cause of your infertility. The accent these days is heavily on IVF, so more couples need to know as much about their situation as possible to ask the right questions and have some proper control over their treatment.

Firstly, it is really important to understand that infertility is merely a symptom that something is wrong. It is not a disease, but usually the result of a disease process. There are numerous causes of infertility and the best treatment is likely to be different in each circumstance. Unfortunately, the massive publicity given to IVF has led to most people believing that it is almost the only treatment and that it is the most successful. This is utterly wrong.

One negative aspect of the IVF revolution means that now couples too frequently rush into IVF. This risk is increased because more freestanding IVF clinics have been established. So there is a real chance of being referred to an IVF clinic where there isn’t the competence or interest in offering anything other than IVF. Regrettably, in the commercial sector, where most IVF is done because the NHS provision is inadequate, the pressure for the clinic to offer IVF rather than any other treatment is strong. Of course, there are excellent ethical practitioners in the private sector, but it can be easier to feed patients into a standard system, a mechanised process such as IVF, rather than to spend time and use skills to look further. IVF practice is immensely profitable, so there is a real risk of IVF being offered when it may not be the most suitable treatment.

IVF does not treat the underlying cause of infertility. Please remember that IVF is just a way of bypassing an underlying problem. As with all medical conditions, merely treating the symptom alone is seldom good medicine.

A rough estimate indicates about one in seven couples will have problems conceiving. Very roughly, failure to conceive is caused by a problem with the woman in just over a third of cases. In rather less than one-third, the problem is because the man is sub-fertile, and in the remainder – around thirty per cent of couples – both partners are responsible. In addition, a substantial number of couples will have what is referred to as ‘unexplained infertility’. But often more detailed testing unveils a probable cause.

It is also frequently said that infertility is on the increase. There is rather less evidence for this. It is probably due to women leaving childbearing until later in life. In advanced countries most women now gain an education, experience, and skills but as a woman grows older natural fertility declines. Undoubtedly more women now seek treatment in their late thirties or early forties.

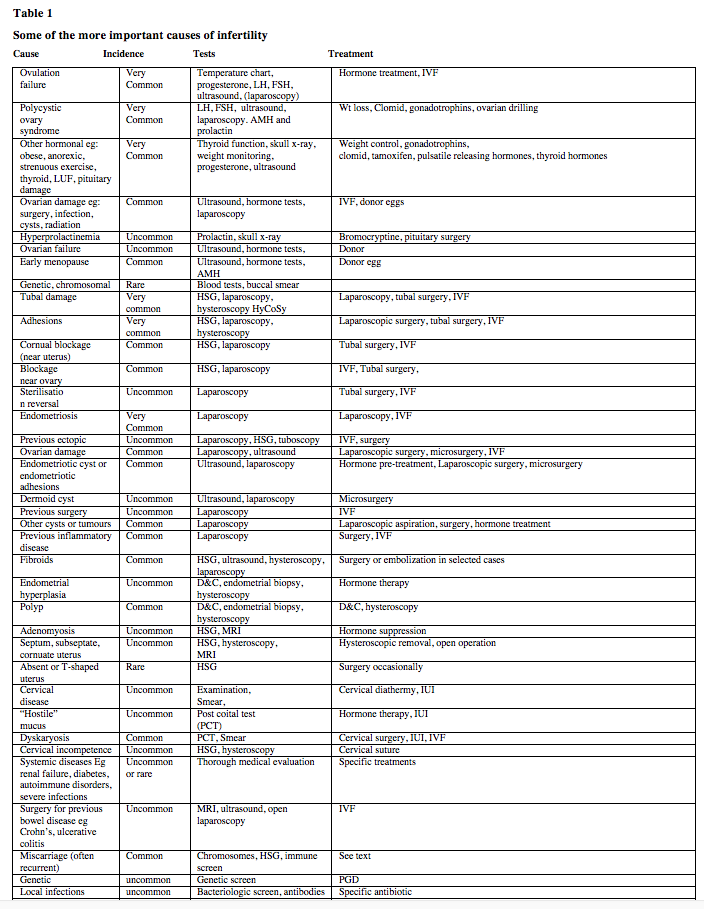

You may be surprised to see that there are so many causes of infertility and the best treatment generally depends on treating the cause. Some more important one are laid out in Table 1. In the UK, the commonest female cause of infertility is a failure to ovulate (around 30%). Damage to the Fallopian tubes is a bit less frequent and possibly accounts for about 25% of female infertility. Endometriosis is found in perhaps 30% of infertile women but does not generally cause infertility; to some extent this depends on the amount of scarring and if the ovaries are involved. Abnormalities of the uterus are quite common but my experience suggests these are not always discovered by many of the routine tests. Reduced ovarian reserve – when only a few eggs are left in the ovaries of usually older woman – is increasingly common because more women are trying to have a baby later in life.

Many couples have two or occasionally more causes for difficulties in conception. In the large London teaching hospital where I used to work, about 12 – 15% of patients had multiple causes. So, for example, many women may suffer from the mild tubal disease as well as intermittent failure to ovulate. Alternatively, many rather sub-fertile women may be married to a man with a lowered sperm count. In general couples with multiple causes are often most suitably treated by IVF.

In about 20% of couples, the only abnormal finding is a poor sperm count. In another 25% of couples, it is a major contributory cause. Occasionally, there may be male infertility even when the sperm looks normal down a microscope possible due to a genetic cause. Problems with sex or difficulty with ejaculation possibly account for around 3% of all infertility.

The causes of miscarriage vary. Most seem due to some problem that is related to a failure of the female system but often the cause is unclear. Moreover, it is highly probable that very many pregnancies are lost very early in development – possibly in the first two weeks. This makes an accurate assessment of the incidence of repeated miscarriage causing infertility quite difficult. So-called unexplained infertility seems to vary greatly. Some surveys suggest that this may account for around 20 – 25% of infertility but this incidence may depend on the extent of detailed testing.

At Hammersmith Hospital in London, with a policy of exhaustive testing, around 10% of patients could be said to have unexplained infertility. Recently, correspondence with professionals who treat women from the strictly orthodox Jewish community in London suggests that the incidence of ‘unexplained infertility’ amongst that population is no more than 2 – 5%. This may be related to pelvic infection as this is uncommon in this group of women possibly because they nearly always have only one sexual partner. Some people with a diagnosis of so-called unexplained infertility may have had a pelvic inflammatory disease in the past but unless a telescope inspection of the pelvis is done the scarring left by infection may not be identified. Unfortunately, laparoscopy (telescope inspection) is now less frequently done under the NHS than it should be. This is because the NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) has, with dubious wisdom, recommended limited indications for undertaking laparoscopy. So doctors feel forced to avoid laparoscopy unless they are very strongly convinced of its necessity. Ironically, this cost-saving approach results in far more patients having expensive IVF treatment than necessary.

Sometimes a diagnosis made with hindsight – that is, after treatment, perhaps with IVF. Once an IVF cycle is completed, we find rather more obscure causes for the failure to conceive. For example, very occasionally fertilisation might repeatedly fail even when there is a normal sperm count. This suggests a sperm problem or occasionally the egg not easily revealed by routine tests. For example, there may be genetic or molecular reasons for egg or sperm to fail to complete fertilisation that only IVF techniques may reveal.

Despite countless breakthroughs in medical science, we still do not understand why some pregnancies will end in tragedy. For most of us, having a child of our own is the most fulfilling experience of our lives. All of us can imagine the desperation and sadness of parents who lose a baby, and the life-shattering impact that a disabled or seriously ill child has on a family.

Professor Robert Winston’s Genesis Research Trust raises money for the largest UK-based collection of scientists and clinicians who are researching the causes and cures for conditions that affect the health of women and babies.

Essential Parent is proud to support their wonderful work. You can learn more about them here.