Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a mental disorder that most often occurs in children. Symptoms of ADHD include trouble concentrating, paying attention, staying organized, and remembering details.

It can be a difficult condition to diagnose precisely. There are no medical tests such as blood tests that can give a categorical answer. ‘Diagnosis’ relies heavily on perceptions of behaviour from school teachers, parents and health professionals. Children with untreated ADHD are sometimes mis-labelled as troublemakers or problem children.

The implications of this – given the impact of ‘ADHD’ on children, parents and society – are enormous.

The sooner parents and health professionals recognise that there are potentially very simple treatments available for conditions that have nothing to do with ADHD, that will result in the child becoming symptom-free, the better.

It is therefore vitally important to rule these alternative possibilities out before a diagnosis of ADHD is confirmed – and certainly, before any medication such as Ritalin or Dexedrine is considered.

Here is more detail on some of the conditions that may produce ADHD-like symptoms

Dr. Merrill Wise, a pediatric neurologist and sleep medicine specialist at the Methodist Healthcare Sleep Disorders Center in Memphis, states that:

“the symptoms of sleep deprivation in children resemble those of A.D.H.D. While adults experience sleep deprivation as drowsiness and sluggishness, sleepy children often become wired, moody and obstinate; they may have trouble focusing, sitting still and getting along with peers.”

Recent research has confirmed Dr Wise’s view that chronic poor sleep results in daytime tiredness, difficulties with focused attention, irritability and frustration, and impulsivity (1).

Similarly, the quantity of sleep in 7-12 year old children was found to be significantly associated with behavioural symptoms including aggressive and delinquent behaviour. (2)

Sleep deprivation makes it difficult to learn (3).

Sleep deprivation impairs mood (Journal of Occupational Medicine, Dec 1992).

More surprisingly, partial, or low-level, sleep deprivation has a bigger effect on behaviour than either short or long-term complete sleep deprivation (Sleep, May 1996).

In summary, all these behaviours caused by lack of sleep are the same ones used to diagnose children with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) and ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder).

This means that many kids are mis-diagnosed with ADHD/ADD when the real problem is chronic or partial sleep deprivation.

When children are identified with symptoms of ADHD/ ADD, often no one thinks to explore the child’s sleeping habits, and whether they might be responsible for the symptoms.

There are other reasons as well that may lead to children being misdiagnosed with ADHD/ ADD, including snoring/ sleep apnea.

Snoring is a possible symptom of a condition called Sleep Apnea. The peak age is 2-5 – coincidentally the same age ADHD is often ‘diagnosed’.

If your child snores they don’t definitely have Sleep Apnea though. Take a recording on your smart-phone and go to see a paediatrician for advice.

Classically, those with sleep apnea snore quite loudly for a bit, then are silent, maybe pause in breathing, then snort briefly, move about, and resume snoring.

Children with sleep apnea do not get sound sleep. They may also get less oxygen to the brain at night. Obstructive sleep apnea can have a serious negative impact on a child’s intellect and behaviour. The common symptoms of sleep apnea are difficulty paying attention during the day, decreased academic performance, oppositional behaviour, and restlessness. All the same ‘symptoms’ as ADHD.

Once these symptoms surface, sleep apnea is often overlooked as a possible cause. Instead, the child is diagnosed with a behavioural disorder — most commonly ADHD/ ADD (Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, Sep 1997).

Another recent study suggesting a link between snoring, sleep apnea and ADHD symptoms followed 11,000 British children for six years, starting when they were 6 months old. The children whose sleep was affected by breathing problems like snoring, mouth breathing or apnea were 40 percent to 100 percent more likely than normal breathers to develop behavioural problems resembling A.D.H.D. (Paediatrics March, 2012)

“Lack of sleep is an insult to a child’s developing body and mind that can have a huge impact,” said Karen Bonuck, the study’s lead author and a professor of family and social medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York. “It’s incredible that we don’t screen for sleep problems the way we screen for vision and hearing problems.”

Large adenoids and tonsils can cause sleep apnea. Infants and Toddlers with sleep apnea are far more likely to end up being diagnosed with ADHD (Dr Merill Wise – paediatric neurologist and sleep medicine specialist, as above). Removing the adenoids and tonsils can clear the symptoms very quickly.

Research shows that children with nighttime breathing problems did better with cognitive and attention-directed tasks and had fewer behavioural issues after their adenoids and tonsils were removed. The children were significantly less likely than untreated children with sleep-disordered breathing to be given an A.D.H.D. diagnosis in the ensuing months and years. (Source – Professor Karen Bonuck – Professor of family and social medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York).

Most important, perhaps, those already found to have A.D.H.D. before surgery subsequently behaved so much better in many cases that they no longer fit the criteria.

“We’re getting closer and closer to a causal claim” between breathing problems during sleep and A.D.H.D. symptoms in children, said Dr. Ronald Chervin, a neurologist and director of University of Michigan Sleep Disorders Center in Ann Arbor.

A child eating too much sugar and some food additives (some people would say ‘eating any’ rather than ‘eating some’) may have their sleep affected. Sugar and some food additives can also directly impact on behaviour – parents are usually familiar with ‘sugar tantrums’ and food additives have a similar effect. It’s best to strictly limit sugar – certainly avoid sugar near bed time – and to cut out food additives altogether if you suspect they effect your child. (Source – National Institute of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements)

Children with sleepwalking, restless leg syndrome, narcolepsy, insomnia, or other sleep problems may also be misdiagnosed with ADHD or ADD (Neurology, Jan 1996).

All of these issues need to be referred to a paediatrician or specialist sleep clinic who can observe your child and recommend treatment.

Restless Leg Syndrome is often managed well with a magnesium supplement. Talk to your Doctor about this.

Magnesium and iron are both necessary elements. If your child is not getting enough from their diet (magnesium e.g., almonds, green leafy vegetables – iron e.g. meat, beans, eggs) you can give them supplements. Up to 80 percent of Americans are estimated not to get enough magnesium in their diets. The most common symptoms of magnesium deficiency are tics, muscle spasms, restless leg syndrome, and anxiety – and sleeplessness and stress result in magnesium being further flushed out of the body.

Iron deficiency is the number one mineral deficiency worldwide. The most common symptom is tiredness.

Magnesium has been called “nature’s muscle relaxant.” It calms the central nervous system and can act as a sedative. Magnesium actually suppresses nerve activity, which leads to a decrease in muscle twitches and jerks, therefore decreasing incidents of night waking. For these reasons, healthy levels of magnesium have been linked to deep, undisturbed sleep.

Supplements of both can be bought at the chemist. Magnesium as tablets, a soluble powder, spray or even as Epsom salts to dissolve in the bath to be absorbed through the skin. Iron supplements as tablets or liquids. Follow the doses recommended.

Omega 3 has been found to have very good effects on brain function in children who were previously deficient. Supplements can be bought over the counter – follow dosage instructions.

Sources – National Institute of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Talk with your pediatrician about a melatonin supplement. Melatonin is a prescribed drug in many countries including the UK and Australia, or available over the counter in many states in the USA. It can help to aid sleep onset but should only be considered if a good sleep routine has been tried with your child for a good period first.

Source – The Sleep Health Foundation in Australia.

A study undertaken by Todd Elder (Journal of Health Economics, September 2010) at Michigan State University found that nearly 1 million children in the USA are potentially misdiagnosed with ADHD simply because they are the youngest and most immature in their class.

Children young for their class are significantly more likely than their older classmates to be prescribed drug treatments such as Ritalin for ADHD.

This is the equivalent of around £320m – $500m a year on unnecessary medication – some $80m – $90m being paid by Medicaid.

Dr Elder states that “if a child is behaving poorly, if he’s inattentive, if he can’t sit still, it may simply be because he’s 5 and the other kids are 6. There’s a big difference between a 5 year old and a 6 year old and teachers and medical practitioners need to take that into account when evaluating whether children have ADHD.”

Elder examined a sample of 12,000 children. The data was from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten Cohort, which is funded by the National Center for Education Statistics.

According to Elder’s study, the youngest kindergartners were 60 percent more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than the oldest children in the same grade. Similarly, when that group of classmates reached the fifth and eighth grades, the youngest were more than twice as likely to be prescribed stimulants.

Overall, the study found that about 20 percent – or 900,000 – of the 4.5 million children currently identified as having ADHD likely have been misdiagnosed for this reason alone. This does not include the misdiagnoses for poor sleep and the other reasons cited above.

“Many ADHD diagnoses may be driven by teachers’ perceptions of poor behavior among the youngest children in a kindergarten classroom,” he said. “But these ‘symptoms’ may merely reflect emotional or intellectual immaturity among the youngest students.”

Lack of sleep can cause ADHD type symptoms but ADHD/ADD & Drugs also causes bad sleep. It’s a vicious cycle.

When parents of children with ADHD are interviewed, they usually identify their kids as poor or restless sleepers (Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Jun 1997). Kids who have been diagnosed with ADHD do wake up more often at night than their peers (Pediatrics, Dec 1987). This can be due to the ADHD, but it can also be caused by the drugs being used.

Poor sleep is a common feature of ADHD — a problem that can be made worse by the use of stimulant medications such as Ritalin or Adderall. In fact, recent studies have reported sleep problems in 25 percent to 50 percent of children and adolescents with ADHD, two to three times the rate of sleep problems in children without ADHD. (Sleep. Aug 1, 2007)

Drugs used to treat ADHD, such as Ritalin, Adderall or Concerta can actually cause insomnia. So if your child has been misdiagnosed with ADHD when in fact they have a sleep problem, the drugs might make it far worse.

“It can become a vicious, compounding cycle,” said Dr. David Gozal, chairman of the department of pediatrics at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, whose clinical practice focuses on children with sleep disorders.

The easiest way to know whether your child’s “ADHD” is actually caused by another problem is to address those other issues first to rule them out.

20 percent of children in the USA – nearly 1 million – are misdiagnosed through being too young for their class. (Source – Todd Elder, Journal of Health Economics, September 2010)

The impact of sleep deprivation, poor sleep etc have not been quantified, but the percentage of children affected is likely to be much higher than the 20 percent from class-age alone.

If your child has ADD symptoms or other behaviour problems, he or she should be carefully assessed for sleep problems first. If sleep disturbances are present, they need to be addressed, regardless of whether or not they are the root cause. If your child is not getting sound, uninterrupted sleep, discuss this with your pediatrician.

The good news is that even when ADD is the correct diagnosis, addressing the sleep issues can dramatically improve the behaviour of the child (Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Apr 1991).

Parents often have no idea how much sleep their child should be having. A study conducted in 2011 by researchers at Penn State University-Harrisburg and published in The Journal of Sleep Research showed that of 170 participating parents, fewer than 10 percent could correctly answer basic questions like the number of hours of sleep a child needs.

“Parents didn’t know what was normal sleep behavior,” said Kimberly Anne Schreck, a psychologist and behavioral analyst at Penn State who was the study’s lead author. “Many thought snoring was cute and meant their child was sleeping deeply and soundly.”

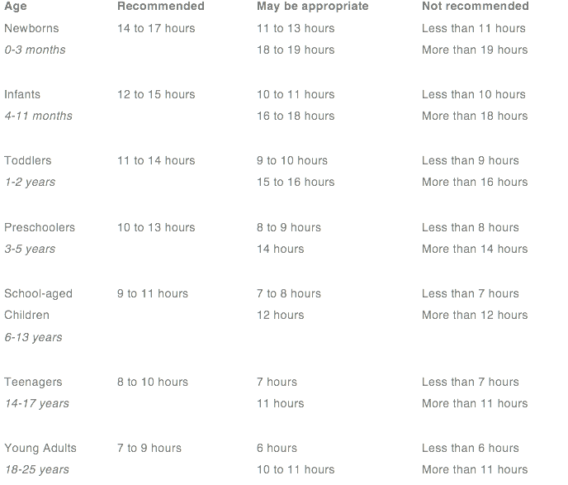

This table shows the amount of sleep recommended for each age group.

Source – US National Sleep Institute.

If your child is having difficulty sleeping enough, as a first step, watch the Essential Parent Sleeping Course. If you need more specific guidance, in the UK, get in touch with Mandy Gurney, our Sleep Expert, via the Essential Parent site.

If you think your child has more profound sleep problems, print out the attached question list and get a referral from your Doctor to a Paediatrician.

If you have any nutrition questions, please refer them to our Nutrition Specialist, Melissa Little, via the Essential Parent site.

We would advise you strongly not to accept a diagnosis of ADHD or ADD until you have ruled out all the other potential factors we have discussed. All of these factors are far easier to treat and your child may lose all symptoms. Remember that taking ADHD drugs can, in fact, make the condition worse if it has been misdiagnosed – since side-effects include, amongst other things, insomnia.

If your child is displaying symptoms of ADHD such as trouble concentrating, paying attention, staying organized, and remembering details, ask the following questions before considering a diagnosis of ADHD.

1) Is my child sleeping long enough? Refer to the Table.

2) Does my child snore?

3) Does my child’s legs twitch when they sleep – sometimes even waking them up?

4) Does my child have any other sleep disorders, including night terrors or sleep walking?

5) Is your child young for their class?

6) Are you or your child’s teacher comparing your child’s behaviour to other children in their class – or to other children the same age?

7) Does your child have a good sleep routine?

8) Do they go to sleep easily and sleep through the night?

9) Do they often wake up early in the morning? At the same time?

10) Does your child eat a healthy diet?

11) Does your child eat a lot of processed food, E numbers and/ or sugar?

12) Have you tried magnesium, iron & omega 3 supplements?

Once you’ve ruled out all the questions above at home, and if the symptoms are still evident, get a referral to a Paediatrician though your Doctor and take this list of questions with you.

1) Might my child have sleep apnea? Take a recording of their snoring or noises with you.

2) Might my child have enlarged adenoids or tonsils? Should these be removed?

3) If my child is sleep walking, has sleep apnea, night terrors, could we be referred to a sleep clinic?

Adams, SK, and TS Kisler. “Sleep quality as a mediator between technology-related sleep quality, depression and anxiety.” Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2013; 16(1): 25-30.

Aronen, A et al. “Sleep and Psychiatric Symptoms in School-Age Children.” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. April 2000, 39(4): 502-508.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Increasing prevalence of parent-reported attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder among children – United States, 2003-2007.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 2010; 59 (44): 1439-43.

Cooper, WO et al. “ADHD drugs and serious cardiovascular events in children and young adults.” N Engl J Med. 2011; 365(20): 1896-904.

Elder, TE. “The importance of relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: evidence based on exact birth dates.” J Health Econ. 2010; 29(5): 641-56.

Hale, L, and S Guan. “Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic literature review.” Sleep Med Rev. 2015; 21: 50-18.

Mayes, R et al. “ADHD and the rise in stimulant use among children.” Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2008; 16(3): 151-66.

Mosholder, AD et al. “Hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms associated with the use of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder drugs in children.” Paediatrics. 2009; 123(2): 611-16.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults.” NICE Clinical Guidelines. 2008: 72:6.

Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, Mar 1996. Vol 3, Issue 1, p 1 – 50. Sleep Disorders in Childhood.

Sleator, EK, and RK Ullmann. “Can the physician diagnose hyperactivity in the office?” Pediatrics. 1981; 67(1):13-17.

Swanson, JM et al. “Effects of stimulant medication on growth rates across 3 years in the MTA follow up.” J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007; 46(8): 1015-27.